Credit: Sotheby’s

Wealth produces the image of a certain breed of human that seems so distant from most of us, yet is distinct in our collective picture. High fashion, poise, elegance—nose turned away from those below them as they attend their galas in favor of some distant, charitable cause. For many of us, this is the perfect vision of a wealthy giver.

Perhaps this is the realm in which many philanthropists fall, but Agnes Gund is not one of them. Being consecrated as potentially one of the “last good rich [people]” out there by the New York Times clearly distinguishes the 80 year-old giver and art collector from other wealthy benefactors. Where some are glad to show off their lavish lifestyle, Gund is afraid of sounding vain and self-centered, and has spent most of her fortune giving back to people and projects that need it more.

From Where the Giver Came

Agnes Gund was born in Cleveland, Ohio in 1938 at the end of the Great Depression. The Gund family, however, were not experiencing these terrible financial times to the same degree as the rest of the country. Her father, George Gund, was president of the Cleveland Trust Family—one of the most prolific banks in America. At 15, she was sent to Miss Porter’s School, where she began to fully realize her love for art from a brilliant history teacher. When her father died in 1966 and left her an inheritance, she began making art acquisitions, starting with a Henry Moore Sculpture of a horse.

Henry Moore Sculpture. Credit: Christie’s

“The arts capture our insecurities, quicken our instincts, guide us through threats,” Ms. Gund says. “They help us know ourselves. They help us know each other. They help us know better.”

But Gund didn’t get into the world of art acquisitions in hope of turning a profit. She did it to simply be involved as a patron. When she ran out of room, or perhaps wanted a new piece of work, she turned them over to museums.

The 1970s were a busy time for Agnes Gund. Early in the decade, Gund’s at-the-time-husband took on a job as the headmaster of a Greenwich, Connecticut school. Due to its convenient proximity to Manhattan, Gund took trips to the city in order to visit museums and a variety of artists. Her involvement in the art scene exploded. In 1976, Gund joined the board of the Museum of Modern Art. In 1978, she went to Harvard to get a master’s degree in art history. She moved on to serve as president of MoMA in the ‘90s, a time considered to be the museums “golden era.”

A Lifetime of Giving Back

From the time Agnes Gund had the money to do so, she was giving it away. Her years of philanthropy—be it through donating to causes, starting her own nonprofits, or otherwise—have made her one of the top philanthropists in New York City.

When a fiscal crisis in 1977 led to extreme budget cuts that practically eliminated arts education in public schools, Gun responded by founding Studio in a School. The non-profit promoted community-based organizations to lead classes in the many disciplines of art, as well as incorporating art education into schools.

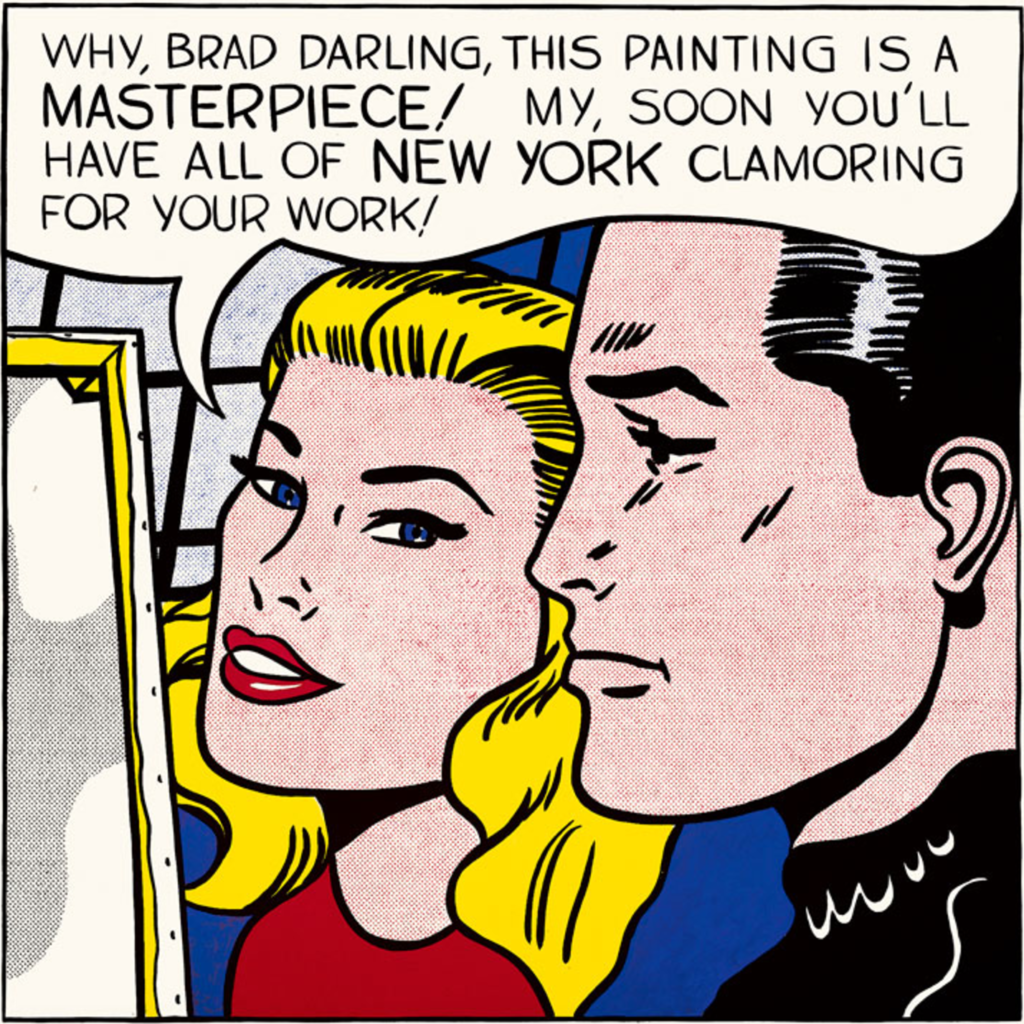

In 2015, Gund saw 13th, a documentary on the racism that come with mass incarceration. Properly stirred by its message, she sold her Roy Lichtenstein painting for $165 million dollars and co-founded Art for Justice, a foundation that provides funds not only for artists in prison, but organizations working towards criminal justice reform.

Roy Lichtenstein “Masterpiece.” Credit: Art Market Monitor

Agnes Gund is a vocal supporter of many sensitive subjects most from her generation would rather not speak of. For years, Gund has donated to AIDS research. She supports a number of abortion-rights groups, as well as women’s rights and often champions the work of female artists and curators, though she hesitates placing any laels on herself such as “feminist.” Race relations and social justice have always been vastly important to Ms. Gund, though even more so now that two of her children have mixed children, and one of them is LGBTQ+. Her dinner parties and social events are diverse and rich in culture.

“She’s a connector,” Lyle Ashton Harris, a renowned photographer, says. “And what she does is not an armchair response or a social gesture. It’s a consistent pattern of putting her money where her mouth is.”

A Quiet Patron

Praise and esteem mean nothing to her. Agnes Gund does not care if she is properly recognized for the amazing work she does for New York and the art community. In 1997, Bill Clinton gave Gund the National Medal of the Arts to honor her philanthropic endeavors. Recently, she accepted an award from the Getty Center for her lifetime of philanthropic achievements. She has been honored by the MoMA and the Wall Street Journal.

Credit: Moomblr

To Gund, these awards are never about her. She praises whoever honored her or any fellow award recipients, just so the focus is off herself. Recently, MoMA exhibited a collection of her acquisitions, but it nearly didn’t happen. She wanted to display a set of lesser-known artists, and was concerned that because the display was under her name, the focus would be off the work being showcased.

When MoMA organized a benefit that would honor her, Gund nearly didn’t allow it to happen. It wasn’t until the museum agreed to invite security and support staff to the after-party with free admittance that she agreed.

Agnes Gund’s work isn’t for herself. It is for everyone else. Though the philanthropy legend says that “guilt” is what drives her to give, that guilt has proven to help thousands of people in ways Ms. Gun couldn’t imagine.