Returning Art to Its Home

Though the Khmer Dynasty lasted roughly from the 9th to the 15th century, a few years of turmoil led to many artifacts from this time period being misplaced. It was over the course of Cambodia’s civil war (1965-1979) that a number of important cultural and religious artifacts disappeared. As a result, Douglas A.J. Latchford’s decades of acquiring Cambodian antiques made him a leading collector.

With a private collection of 125 works (valued at $50 million), Latchford became one of the world’s leading experts on Khmer antiquities. His home in Bangkok was lined with precious Cambodian jewels, golden crowns, and statues. In his lifetime, he co-wrote three books on his holdings (and the holdings of other private collectors), all of which became crucial core reference works to studying Khmer art.

But with years of collecting under his belt came questionable methods—a problem several members of the art collecting community have come under fire for. His propensity to donate the occasional item to the Cambodian government always earned him high praises (he was even granted the equivalent of Cambodian knighthood in 2008), but they weren’t enough to shadow his potentially dubious habits of acquisition. In 2019, federal prosecutors in New York charged Latchford for trafficking in looted Cambodian relics, most prominently during Cambodia’s civil war, as well as falsifying documents.

Douglas A.J. Latchford, Credit: The Art Newspaper

The prosecutors said he “built a career out of the smuggling and illicit sale of priceless Cambodian antiquities, often straight from archaeological sites.”

Though the accusations were never proven, they weighed on Latchford’s daughter, Nawapan Kriangsak, and only grew heavier when Latchford died at 88 in the summer of 2020. Suddenly, Kriangsak found herself the owner of the 125 piece collection of ancient Cambodian artifacts that not only carried the history of a nation, but potentially a history of illegal trade.

Despite the controversy, Kriangsak claims her father’s collecting habits were not out of greed, but out of reverence. She says the collection was created in a “very different era,” and that the world the collection was born into is not the world it currently lives in. She does not believe the best place for this collection is in her living room. She believes it belongs in the country they were taken from, “where the people revere these objects not just for their art or history, but for their religious significance.”

“Maybe it’s my Buddhist background that made me start to look at things a little differently,” Kriangsak says. “And it didn’t come easily. But in the end I felt, ‘Why should it be just a part of the collection when it should be something really stunning — the entire collection.’”

This comes in direct defiance to the legal team and advisors that worked with her father. Latchford was reluctant to return the collection completely, but Kriangsak knew the move would be best for her in the long run. The family had already spent two years coming up with a plan to repatriate the artifacts, and upon her father’s death, she set up their return to Cambodia to be studied by Khmer scholars and displayed in a new museum in Phnom Penh.

A bronze decoration from late 12th century boat from the collection. Credit: Royal Government of Cambodia

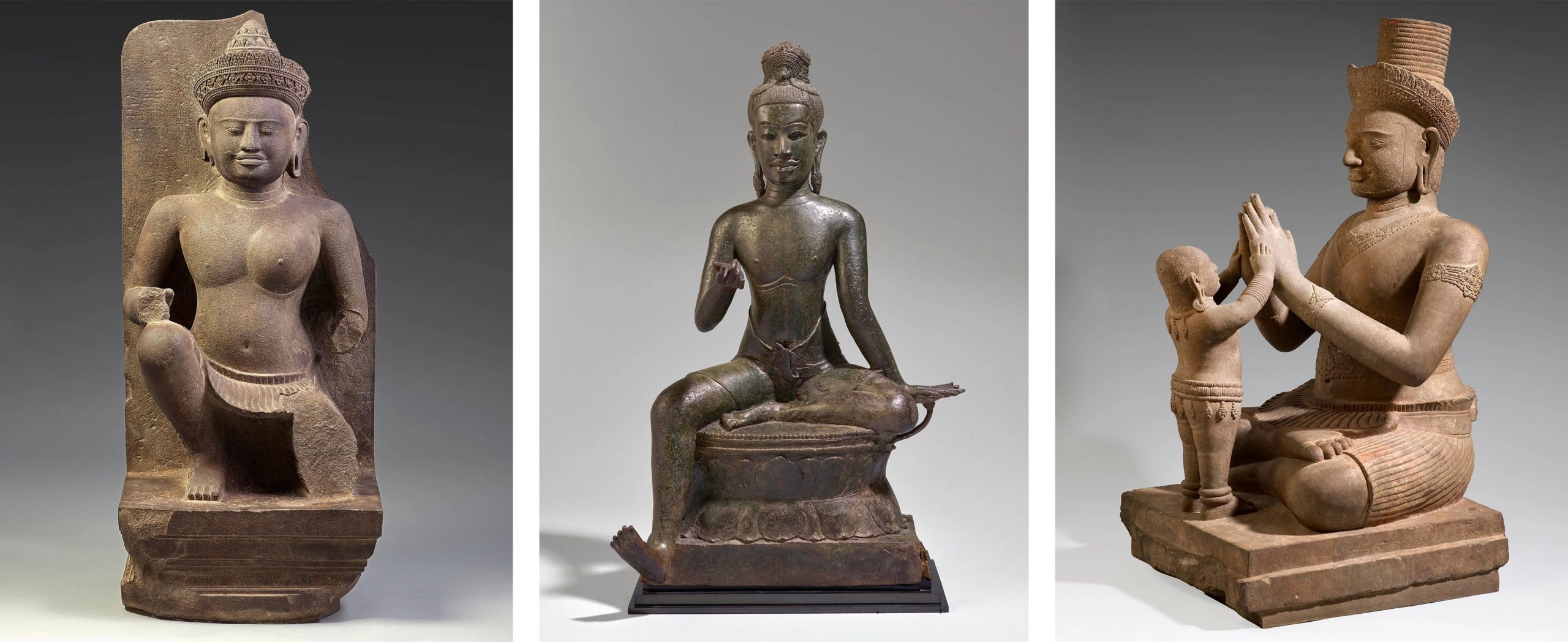

A few items of the collection. Credit: The Cambodia Daily

Though Cambodian officials never directly addressed their thoughts on the potentially illegally acquired artifacts, they were floored by Kraingsak’s kind gesture. When the museum and display are ready, the collection will wear the name, “the Latchford Collection.”

“Happiness is not enough to sum up my emotions,” Cambodia’s minister of culture and fine arts, Phoeurng Sackona, says. “It’s a magical feeling to know they are coming back. These are not just rocks and mud and metal. They are the very blood and sweat and earth of our very nation that was torn away. It is as if we lost someone to war and never thought they’d come home and we are suddenly seeing them turn up at our door.”

Out in the world, there are potentially thousands of culturally significant art pieces that were illegally acquired. While 125 pieces seems like a small amount in comparison, it is an important step in the right direction.

“It’s a message,” Sackona says, “that the statues should be home on our soil — not locked away in some private living room but here in Cambodia where visitors from around the world can see them.”

MORE INSPIRING STORIES

Related

7-Year-Old with “Incurable” Condition Overcomes Her Diagnosis

When Evie-Mae Geurts was just a few months old, she was registered as blind. It’s a difficult prognosis for any parent to hear, that their child will live a more challenging life than others. It’s hundreds of times more difficult when that diagnosis is compounded with...

Anonymous Donor Pays Off Tuition for Graduating Class at Wiley College

Graduation is an equally exciting and terrifying time for many college students. While the time should be spent celebrating the massive achievement, many are fraught with worries of the future—namely, how they are going to overcome the debt they’ve accumulated. Wiley...

Bartender Saves Family from Rip Current

Cape Town, South Africa, is well-known as a tourist destination in part for its gorgeous beaches. People travel to the area for its nature, its culture, and maybe to end the day with a drink on the water. That is precisely how Clair Gardiner and her daughter, Arya,...

Join

Subscribe

GET INSPIRATION & BEAUTY RIGHT IN YOUR IN BOX!