Credit: Brothers of the Book

moral

adjective

- Concerned with the principles of right and wrong behavior and the goodness or badness of human character. “the moral dimensions of medical intervention”

- Holding or manifesting high principles for proper conduct. “he prides himself on being a highly moral and ethical person”

noun

- A lesson, especially one concerning what is right or prudent, that can be derived from a story, a piece of information, or an experience. “the moral of this story was that one must see the beauty in what one has”

- A person’s standards of behavior or beliefs concerning what is and is not acceptable for them to do. “the corruption of public morals”

Credit: Google Dictionary

Morals: Right or Wrong, or Right and Wrong?

Though likely not conscious, there is a certain factor that influenced every single one of our day-to-day decisions—small ones, like whether or not we’ll have chicken for lunch, and big ones, like whether or not we’ll take a certain job: morals.

Because of a vegan’s moral code, chicken would be out of the question. A hardcore, right-wing conservative may be hesitant to accept a job at NBC . While perhaps someone who eats meat wouldn’t be morally opposed to eating a salad (though who can really say), a devout, left-wing liberal would be just as unsure about taking a job at Fox News.

Credit: Money Crashers

Both of these people have strong moral foundations that shape how they interact with others, yet, in many cases, both of these people think the other is wrong— perhaps even a bad person— for harboring these different beliefs. So, what makes someone a moral person? Is it simply doing what you believe is right? But if it was as simple as that, wouldn’t that make monsters like the fictional serial killer, Hannibal Lecter, a “moral” individual, as he didn’t think killing and eating other people was wrong?

A study by Skitka, Bauman, and Mullen tells us that most people believe that, for something to be moral, it must fulfill a set of five attributes: the moral must be universal, reflect one’s self conception, be objectively true or similar to facts, demand action, and cannot be altered based on what authorities deem is or is not moral. Assuming this study is correct and these five factors are a main influence our beliefs on morals, how is it possible people can have an intense set of beliefs that shape their behaviors and think someone else with a different set of intense beliefs is wrong?

It is all based on how their morals were molded in the first place.

Credit: Gender&LitUtopiaDystopia Wiki

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy splits morality into two related, but entirely unique, fields: descriptive, and normative. Morals described normatively are a code of conduct that is put forward by all rational persons, such as labeling child abuse or murder as wrong (obviously, Hannibal Lecter isn’t a “rational person” in the traditional sense of the phrase). Even with very different social beliefs, a majority of the population can agree on these morals.

Describing morals descriptively, however, leads to the many discrepancies we see between groups of people, as these codes of conduct are enforced by one’s society. This could be the town in which they grew up, or the religion they were raised to be a part of. If you’ve read even one psychology paper, this clearly lines up with the belief that the environments we are raised in have a massive impact on the person we grow up to be.

This explains why certain societies put forth a certain set of beliefs that others can’t believe are acceptable. There are still a few tribes in remote locations across the world that practice cannibalism. To them, this is an entirely normal practice—though murder is still a punishable offense. To a western tribe of financial advisers, cannibalism is among one of the worst crimes someone could commit. Does that make our American civilization more “moral” than these tribes’?

Credit: IBM

Some would say yes—validating that sort of behavior isn’t right. Others, namely psychologists and sociologists, would argue that you can’t compare the morals of two societies when their cultures vary so much. Some of our practices that we find completely mundane may very well be heinous to the tribe. The only morals we can debate are the ones our population actively practice.

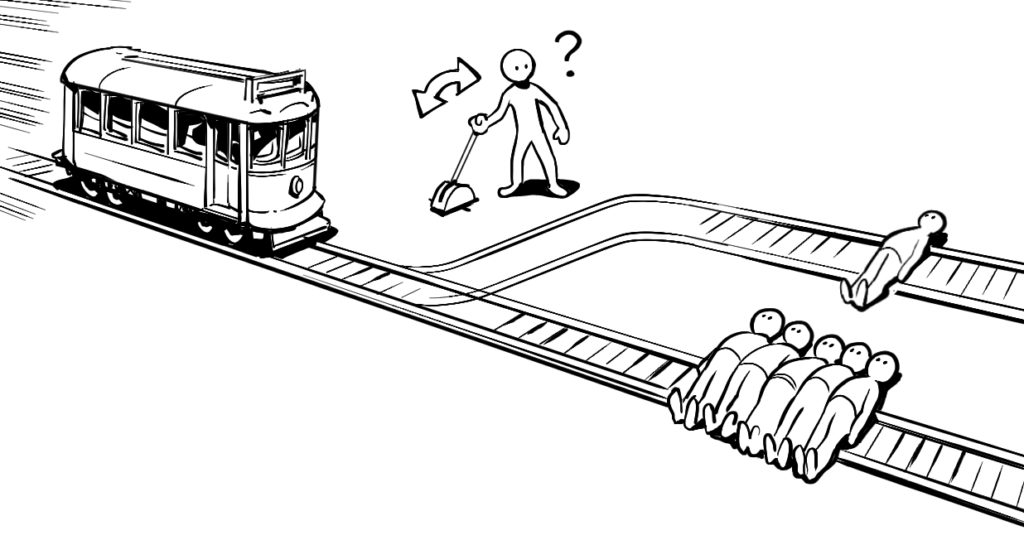

Even so, morals are not necessarily black and white. There is a grey area many of our decisions teeter on. The famous train dilemma and its many variations illustrates this well: You are watching a train. It is going to hit a group of five people, but if you pull a lever, you can save the group. In the process, however, the train will be diverted and hit one person. What is the right choice? Those with a deontological belief system would say that pulling the lever is wrong. Those with a more utilitarian outlook would say pulling the lever is the only choice.

Credit: CreateDebate

While it is unlikely any of us would find ourselves in this exact situation, the bones of the dilemma remain true—the deontological beliefs aren’t wrong. Neither are the utilitarian beliefs. But with such a difficult decision to consider, can any choice truly be the right one?

Let’s scale back a little. Think of the celebrities that donated large sums of money to help those effected by the California wildfires. Now think of the boy who used his own time and money to work hard and help his late-best-friend’s family afford a tomb-stone. Is either’s effort to help someone else more moral than the other? A utilitarian would likely say yes—because the celebrity is helping more people with their donation, their effort is more impactful. A deontologist might disagree—the boy is making a direct difference in the lives of someone else in spite of his limited resources, so his cause is more moral—but making said decision would be difficult one, as who can say which is the “fairer” option?

Credit: New York Times

Can we really discern that one’s good deed is better than someone else’s? In the previous column, it was concluded that, when it comes to gifts, it is the thought that counts. Why doesn’t this seem to be the case with moral decisions? We hold people like Agnes Gund, who gives all her money away in the now, at a higher standard than we do Jeff Bezos, who hasn’t given enough. But does that make Gund a more moral person? Is she making the “right” decision, while Bezos is making the “wrong” one?

In the end, it seems doing what is right and wrong isn’t simply a question of one’s morals. If we keep asking who or what is right and wrong, we’ll talk ourselves in circles. An entire society cannot agree on what is moral 100% of the time. What it comes down to is the singular person.

Credit: Nicola Morgan

If someone makes what they feel is a moral decision, they will be happier than someone who does nothing. They will hold themselves in higher regard. It doesn’t matter if they give five dollars to a homeless person, or if they donate $100 to a shelter. It’s about doing what feels right. The world around them cannot dictate what that may or may not be.